Dunkleosteus terrelli, an armor-plated fish that lived in the shallow subtropical waters of the Devonian period, about 360 million years ago, is one of the most widely recognized fossil vertebrates due to its large size and status as one of the earliest vertebrate apex predators.

New research by Case Western Reserve University scientist suggests the length of this prehistoric predator may have been greatly exaggerated.

Dunkleosteus terrelli is a large arthrodire placoderm fish, but also best known from the latest Devonian Cleveland Shale of Ohio, the United States.

This species is one of the most recognizable prehistoric organisms and is by far one of the most widely known Paleozoic vertebrates, only comparable to the Permian stem-mammal Dimetrodon limbatus in this respect.

Dunkleosteus terrelli’s popularity largely stems from its unique morphology, which includes an extensive dermal skeleton, blade-like jaws, and large size.

These features, as well as its great geologic age, result in this species often being considered ‘one of the first vertebrate superpredators.’

However, in spite of its prominence in paleo pop culture, relatively little is known about Dunkleosteus terrelli as an actual animal.

“Dunkleosteus terrelli is already a strange fish, but it turns out the old size estimates resulted in us overlooking a lot of features that made this fish even stranger, like a very tuna-like torso,” said Case Western Reserve University Ph.D. student Russell Engelman.

“Some colleagues have been calling it ‘Chunky Dunk’ or ‘Chunkleosteus’ after seeing my research.”

|

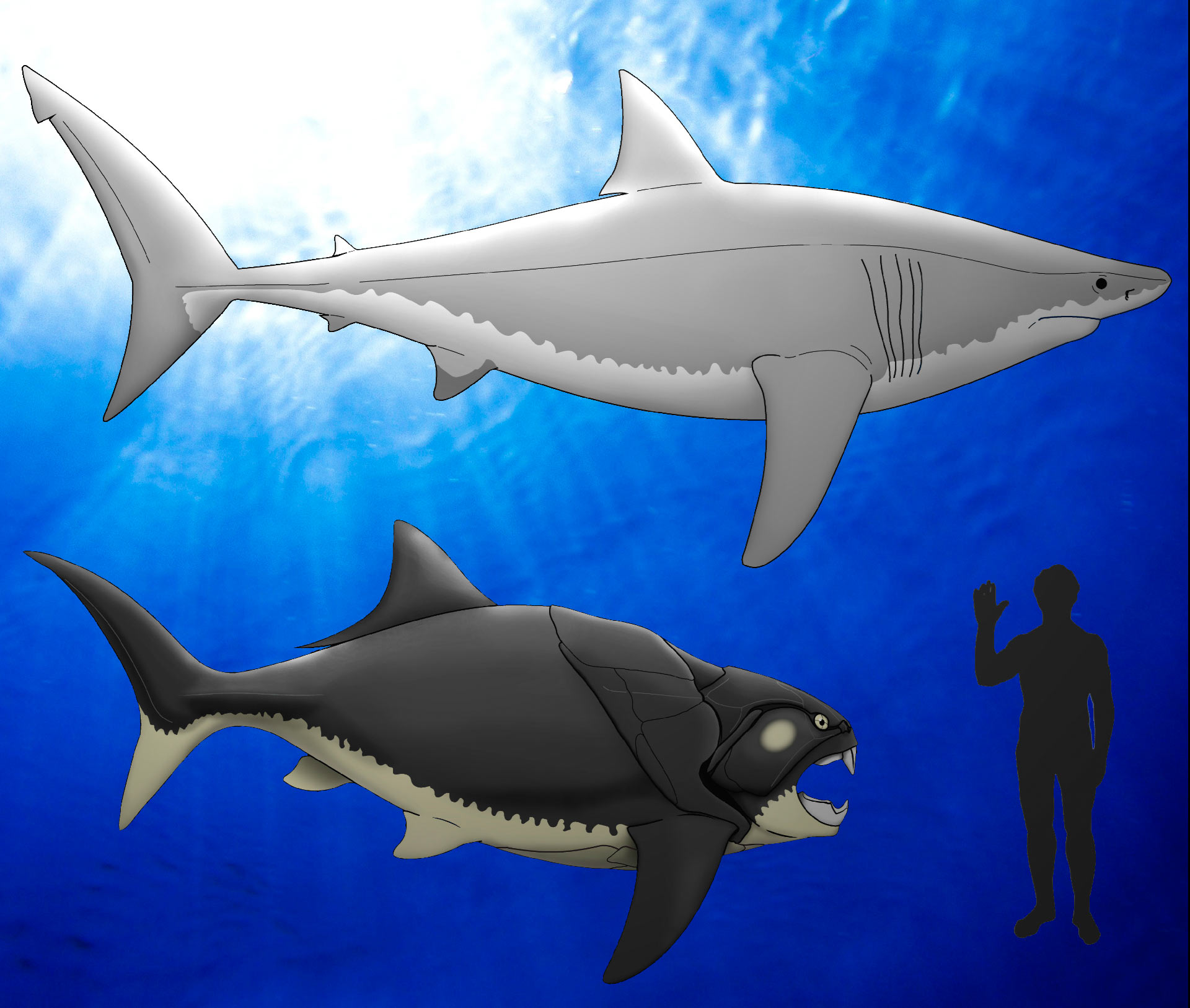

| Reconstruction of the largest known specimen of Dunkleosteus terrelli, compared to one of the largest reliably measured specimens of Carcharodon carcharias; a 1.75-m-tall human for scale. |

Unlike modern fishes, arthrodire fishes like Dunkleosteus terrelli had bony, armored heads but internal skeletons made of cartilage.

This means only the heads of these animals were preserved as fossils, leaving the size and shape a mystery.

Engelman proposes estimating the length based on the 61-cm (24 inch) long head, minus the snout — considered a way to measure that’s consistent among groups of living fishes and smaller relatives of Dunkleosteus terrelli known from complete skeletons.

“The reasoning behind this study can be summed up in one simple observation. Short fish generally have short heads and long fish generally have long heads,” Engelman said.

Based on that method, he concluded Dunkleosteus terrelli was only 3.3 to 3.7 m (11-13 feet) long — much shorter than any researcher had proposed before.

“Dunkleosteus terrelli has often been reconstructed assuming it had a body shape like a shark,” Engelman said.

But a shorter body and shape of the body armor also meant Dunkleosteus terrelli was likely much chunkier.

“A 3.3-m-long Dunkleosteus terrelli is essentially the same weight as a 4.6-m (15 foot) great white shark,” Engelman said.

“These things were built like wrecking balls. The new proportions for Dunkleosteus terrelli may look goofy until you realize it has the same body shape as a tuna…and a mouth twice as large as a great white shark.”

These new size estimates also help put Dunkleosteus terrelli in a broader scientific context.

This fish is part of a larger evolutionary story, in which vertebrates went from small, unassuming bottom-dwellers to massive giants.

“Although the reduced sizes for Dunkleosteus terrelli may seem disappointing, it was still probably the biggest animal that existed on Earth up to that point in time,” Engelman said.

“And these new estimates make it possible to do so many types of analyses on Dunkleosteus terrelli that it was thought would never be possible.”

“This is the bitter pill that has to be swallowed, so that now we can get to the fun stuff.”

Sources:

Russell K. Engelman et al. 2023. A Devonian Fish Tale: A New Method of Body Length Estimation Suggests Much Smaller Sizes for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira). Diversity 15 (3): 318; doi: 10.3390/d15030318